Remember the streamlined train, that was an original railcar, converted to a streamliner by Budd, with a Besler Steam truck? Besides being too heavy, what were the other major maintenance problems with it? Not too much has been mentioned about the flex coupling between the flash boiler and steam truck. The short 7" stroke of the compound steam pistons, and the 8 stroke per wheel revolution showed promise for speed, tractive effort , etc…

Part of the issue with it, in my opinion, was that it had a very long wheelbase and relatively primitive suspension and guiding. I will have to see if I can find good illustrative pictures of the arrangement – they do exist – as it has been many years since I looked at this.

As I recall, the little engines in the trucks shared some of the detail design with the engines for the B&O W-1 constant-torque locomotive, and would have been susceptible to a range of shock and contamination issues in service on typical dusty jointed rail and environmental conditions.

There seem to be many designs of railcar and lightweight train construction (the original McKeens and the Baldwin RP-210 for ‘Train X’ being early and late examples) that carried complex reciprocating machinery on a truck frame with only relatively hard primary suspension. I’m still looking for the actual Locomotive Drive 1 and 2 Westinghouse patents for the PRR S2 chassis, as there were detail design changes from Alben’s original that may have produced similar unsprung-weight concerns in the inner-axle gearcase design as built; a critical issue of concern being whether counter-load springs were provided at the outer ends of the ‘balanced’ trunnioned gearcase to lower its vertical effective polar moment of inertia and limit the effective unsprung mass effects on the suspension of the middle axles (equalization of which might be an interesting dynamical design exercise in itself, as the locomotive was not initially designed with Timken rods between #2 and #3 driver pair, and therefore some of the suspension ‘lessons’ from the first T1s might have been seen as relevant even with effective ‘conjugation’ of the driver groups).

i wonder if the problems you mentioned would have been eliminated if the railroad had accepted a Zephyr like installation for the Besler as originally proposed by Budd? The W1 used a “v” piston design mounted above the wheel, to transfer the downward thrust to the wheel - rail surface. The Besler Budd used a horizontal thrusting pistons. And as I recall a sealed, oiled gearbox that should have kept clear of rail dust…

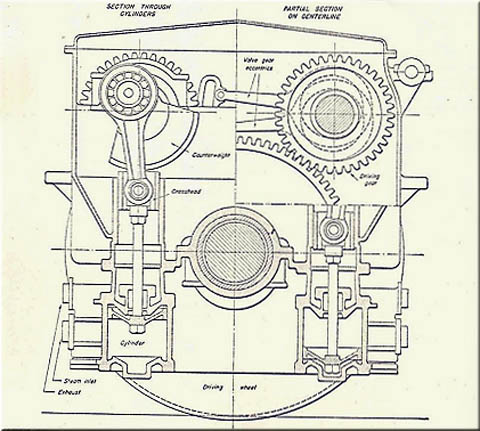

It did not; the pistons act vertically on either side of the axle, slung low down for reasons that don’t hold up well when you look at unsprung weight and primary suspension. See patent 2134072 or the motor detail drawing:

I think you’re remembering the Roosen motor locomotives, which used comparatively large V-2 engines alternating outside the gauge entirely, acting inward on adjacent wheel spokes in a one-ended version of quill/cup drive. In my not-so-humble opinion this was a much more promising approach than the Beslers’ even if it needed better conjugation of the physically-independent axles to get the effect of the ‘constant torque’. One of our great national shames was cutting up the locomotive we brought over here as ‘reparations’ after the War, merely for political Korean-war ‘optics’…

I have wondered whether the Paget locomotive drive (with better materials and a workable valve system) would be a better thing to try in a constant-torque express locomotive. That is a comparatively very-short-stroke design with relatively little rod angularity (and the angular vertical moments on the axles balanceable) with most of the thrusts longitudinal and affecting augment comparatively little. With four axles and somewhat larger wheels, and maintaining the outside-bearing frame, a very interesting and stable locomotive with great modularity in the drive and steam connections could have been developed, and worked at as high a pressure as the Emerson watertube box could cost-effectively utilize…

Also in my opinion, the ‘better’ use of a Besler high-pressure approach eould be to frame-mount the motors, with rigid steam and control connections, much as the engines in a RDC are mounted, with comparable drive (ideally via the Bowes-drive railcar variant as seen in the collection at ISM in Philadelphia) using Cardan shaft to axle drives with spiral-bevel, hypoid, etc. optimized to use counter pressure braking in backdriving. That would give you high-speed and high acceleration torque with very little complexity other than the self-contained Bowes unit (which also coordinates reverse outside complicating the steam-engine valve gear) together with very effective dynamic snd blended braking to simplify issues with friction brake proportioning, integrity, overheating and shoe/pad and wheeltread life; not incidentally also allowing both easy towed operation and electric station access with the flash boilers idling, both of which were important potential considerations in the East.

You have the wrong patent, wrong design

https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/74/a3/bc/73987f08b268c0/US2155781.pdf

in any event, suspect the pressed on cranks were problematic as well as the frequent stops and grades the New Haven required. Also the pneumatic controls for the Stephenson valve gear were sketchy. However the 8 strokes per wheel revolution helped equate to the action of a 8 pole motor, helping to aid smooth acceleration, adhesion…

BTW, this is the W1 “V” design to which I referred

https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/pages/US2235957-1.png

There is no particular functional difference between the illustration in the patent you provided and the detail drawing from coverage in the trade-press article (which I had understood to be a construction drawing for one of the motors actually built for the locomotive). Both are not V engines in the accepted sense of the term, as they do not share a common crankshaft; they are effectively dual-inline (with the 2 cylinders each) driving on a common bull gear, and the resultant of piston thrust is upward, not downward in either design (I suspect it does not matter for adhesion as the reaction moments are entirely constrained by the gearcase structure). Only incidentally are they angled at 30 degrees; a true V engine would probably not allow for placement of the main axle in the V as the patent calls for.

The patent number I provided, as well as the illustration, are taken from an online reference quoting the article – I did this to facilitate locating the reference, as I don’t maintain a Web site or image stash that furnishes URLs the current Kalmbach software will recognize. I doubt, with their often expressed concern over unattributed images and material, that their ‘new and improved forum experience’ will feature any inline embedding at all.

I have not looked carefully at the rail car patent drawings yet, but it was my impression that the powered axles in it were not conjugated mutually some multiple of 45 degrees apart. If not, it’s likely to me that slipping would tend to put the engines in phase (comparable to the effects with larger Mallet-pattern articulateds) and much of the eight-pulse-per-revolution smoothness then reduced in practice. I do not know if that was observed in operation of the railcars, but it would have been difficult to check both by inspection and in operation.

If you have detail drawings for the flexib

Great info…Besides design errors, I am still seeking info on what kept breaking and the resultant repairs to the Budd Besler unit…I seem to read a lot about them continuously being broken but not much about why…

Although the W1 was never built, it appears moving the pistons inside the wheels were an improvement over the Budd Besler unit that had exterior pistons and weak pressed on cranks…

The idea of having exterior pistons, valve gear and gearing to make it “easier to service” may be an oxymoron for being “serviced more often” …

To visualize what is being talked about

Nice pic…always have trouble posting pics to the site.

The purported breakdowns for this train were outlined in the book, “New Haven Power, 1838-1968” by JW Swanburg…of which I don’t have a copy…can anyone help out with what it says…?

It was a tremendous improvement. On the other hand, I think the Besler unit was intended as an ‘underfloor power unit’ that would maximize interior room (and that could be changed as a unit in just a few minutes for servicing).

The outboard cranks avoided the need to machine (or worse, fabricate) a cranked axle for that service. In my opinion, the cranks could have been given offset keys secured with an analogue of Superbolting if the issue with pressed cranks could not be resolved with better shop practice. As you renember with the dry ice and heat, the right combination could be applied to axle fit and crank, with the key serving as an effective guide holding theoretical correct quarter while the crank was driven on to correct depth, then the pins finish-machined “on a quartering machine” to be right.

There were detail-design flaws in the railcar set, perhaps carried over from its pedestrian beginnings. From what I remember of the Besler truck, its ‘advertised’ 70mph capability was right about what the suspension could safely handle; personally, I think much better secondary suspension would have been needed, perhaps with better lateral control as well, over that power truck.

Bought a copy of Swanberg to check; we’ll see what he says. Literally 5 minutes after I placed the order, someone listed on Amazon for 25% less. Ah, the pains of research!

The Besler Budd steam truck was designed for low center of gravity and motorcar application…

On another note, seem to remember a 3 piston locomotive design, having both inside and outside pistons. Things were fine until having to work on the inside piston…

http://kesr-mic.org.uk/resources/The+Modern+3-Cylinder+Locomotive.pdf

That’s a good reference, which I had not seen before. It is peculiar that Holcroft makes no reference at all to American practice, where some of his ‘desirable reasons’ for adoption were observed nearly a decade earlier, and where three-cylinder construction would become a major design point for one builder (Alco) stadting right about the time of this paper.

Note the stated difficulties with three cylinders on reciprocating engines are not so much with the inside pistons, but with the inside piston valves. Were a Budd-Besler truck to be made with three (very small!) cylinders, the power-piston access would (I think) be little worse than for the outside cylinders (the heads of which face each other). Presumably the inside valve would be driven by an eccentric as all three valves, being Stephenson, could have common lead change as mentioned.

The chief problem I see – and I suspect it is related to the real problem with the press crank fits – is that the axle drive is unconjugated. This is a common issue in the original Besler constant-torque, and that its effects were under appreciated can be seen in the example of the PRR duplex ‘double Atlantics’ which were notoriously slippery with twice the conjugation.

Personally I think there was not enough consideration of the practical unloading of axles due to shock or track geometry. In the PRR duplexes it was found that an event like a low rail joint or momentary adhesion fault could greatly decrease the effective adhesion of an individual drive wheel. Were this wheel conjugated (via rods) with 5 or 7 others this would be comparatively less of an issue, but when there are only three, with high horsepower capability in the engine, the chance for a slip even at ridiculously high nominal FA is still extreme, and if the valve gear gives accurate events up to high cyclic you’ll have the risk of high-speed slipping comparable to those Franklin results of ‘140mph’ or h

Was curious if there was any follow up after your purchase and review of Swanburg?

New user name. I’m sorry to see how much of the older posts in this thread have been truncated… not because I was the one who wrote them.

Swanburg, as I recall, did not have much to add as far as technical description, although there are some interesting pictures with detail for those who appreciate how the engineering and construction were done. I did not see any reference to this train in the Besler papers from the Steam Automobile Cljub of America (SACA) which isn’t really surprising given their focus – the B&O constant-torque, the theory and practice of Besler tubes, and the steam airplane aren’t there either.

If you enjoy things New Haven, the book is something to consider (it was a source of one of the best stumping questions on one of the quiz threads in Classic Trains) BUT take your time, browse Abe Books and Amazon, and wait until a used copy comes up for a reasonable price – that being much less than the average vulture-bookseller profit price.

I don’t understand the reason for that, and I wish that someone would explain it.

Rich

I believe the truncation issue was touched on by at least one of the Firecrown crew as a result of a reasonable effort to capture the contents of the old forum. One of the reasons for leaving the old forum open for reading was to allow people to capture truncated posts.

My recollection was that posts went overboard with quoting. The two ways of replying on the new forum make it less necessary to quote.

So was it just an issue of memory overload?

I don’t know enough of the details to offer anything more than slightly educated guesses. What comes to mind is that the software used had a hard coded buffer size to keep storage space in reason considering that the MR and Trains mag had 2.8million posts in just those two forums.

Yeah, that makes sense. 2.8 million posts!?! Wow, who knew? That would have been a great trivia question. Thanks for that post.

Rich