Ya know, I’d pay a few bucks (say 20, or so) for a good video showing the guys and gals assembling brass steam engines. Just sayin’…

I’ll also mention that you might want to go the epoxy/superglue route. I kitbashed a couple of Mantua locos that way, and the only soldering I did was the coiled air pipes under the running boards. Of course, you can’t really solder onto the Mantua boilers anyway. Or their plastic cabs. Or…

But, getting back to soldering brass:

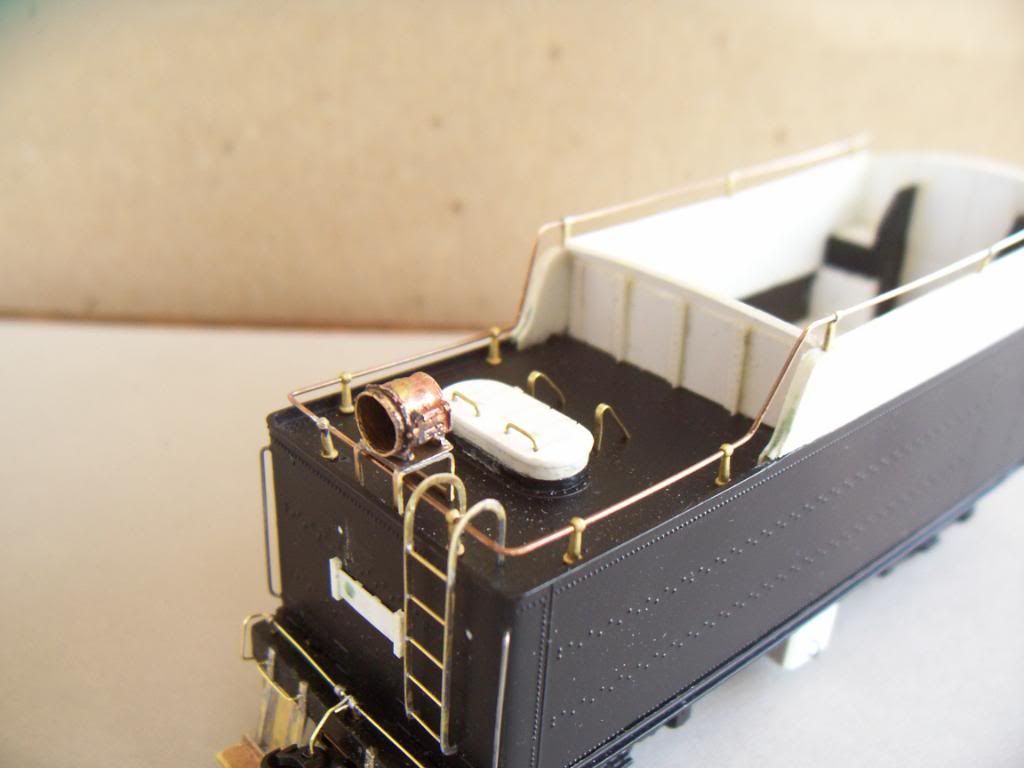

Silver solder (real, not Tix, etc.) comes in several different melt temperatures. You need a torch. I used two grades of it once when I was soldering the feed pipes to a low-mount Elesco feedwater heater. I used the higher temp for soldering the larger pipes on, and the low for the smaller. Properly done, the joints are incredibly strong and are stable at lead solder temperatures. Once I was through soldering, I essentially had a one piece item. Very comforting.

Tix and similar other high-strength–low temp solders have their uses. But, so far, I haven’t needed/used them. I would certainly keep them in mind.

For tin/lead solder, the easiest-best all-around tool is the resistance soldering rig. WITH PROPER PLANNING, the heat goes EXACTLY where you want it. So far, I’ve used mine to solder wires to the bottom of track with plastic ties. Sweet! The American Beauty costs about $500, though. NOT sweet!

When I made the above mentioned coiled air pipes, I used an electric soldering gun. Almost surprisingly, it worked. Now, I’d probably use a small soldering iron just for the decrease in clumsiness. Though, actually, this might be a job for a torch because you kind of want to set up the whole assembly in some sort of jig and just gently touch it with heat. The resistance tool would probably do well, too.

I’ll remind you that one mistake and your grandfather’s work can b