MTA Employees’ Newsletter At Your Service , August 2004

Lewis B. Stillwell (1863 -1941)

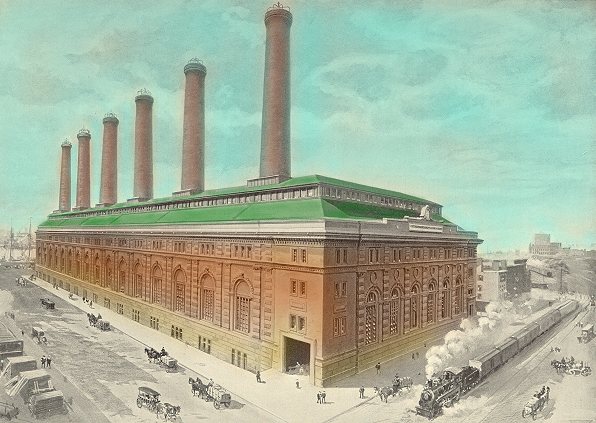

Lehigh graduate Lewis B. Stillwell was hired by Westinghouse to show that AC could be generated more cheaply than Thomas Edison’s DC, transmitted long distances and converted back to DC for local use. Assigned to lead the giant Niagara Falls Powerhouse #1 project in 1895, Stillwell made the controversialdecision to operate the new system at (a low) 25 cycles per second. This set the standard for bulk power generation, transmission and conversion for the early 20th Century. When the Chicago and New York Els were electrified after Stillwell left Westinghouse in 1897, he oversaw construction and activation of huge, 25-cycle powerhouses, with substations along the rights of way to change AC to 600-volt DC for the third rail. This led to his joining the Rapid Transit Subway Company as director in 1900, then planning the imposing powerhouse on West 59th Street in Manhattan, and the eight substations that powered New York’s new subway in 1904. (article by Robert W. Lobenstein, NYC Transit General Superintendent of Power Operations)

The Electrical Journal, October 1, 1895

At the annual banquet of the Western Railway Club, held in Chicago September 18, Mr. L. B. Stillwell, of the Westinghouse Electric Company, in responding to the toast “Electricity as a Motive Power for Surface Railways,” said in part:

Electricity never stretches, never breaks, weighs nothing, can be subdivided indefinitely with great ease, can turn corners without loss. It can transmit large amounts of energy at pressures easily controlled along wires of moderate size, and it never freezes. Its loss by friction is comparatively insignificant, and its other losses in comparison with every other known agent are almost negligible.

It is interesting to note that in employing electricity we are