Yesterday evening and again this morning, I did some further research on this entire subject and prepared a draft of a post which required a bit of proofreading before posting. I put aside the draft due to a doctor’s appointment, but I am now home and have proofread the post which reads as follows.

I believe that I have finally pinpointed the exact spot where the New York Central and Pennsylvania mainlines split off from one another.

Let me clarify my original intention in starting this thread. Way back in 2005, I learned about the race east from Englewood Station in Chicago between the NYC and PRR. What really made the race exciting was that each railroad had two mainline tracks and those four tracks ran parallel, side-by side. At some point about 5 to 6 miles east of Englewood Station, the mainline tracks of each railroad began to split off from one another although those tracks were still relatively parallel to one another. There is plenty of commentary online to indicate that the race ended at the point where that split occurred. So that was my question. Where exactly did that split take place?

The replies to this question have been most helpful including gpullman, matt_mcc, timz and MidlandMike, along with encouragement from Woke_Hoagland. But the topographical maps from MidlandMike sealed the deal along with Ed’s (gpullman) identification of Columbia Malting as the point of separation.

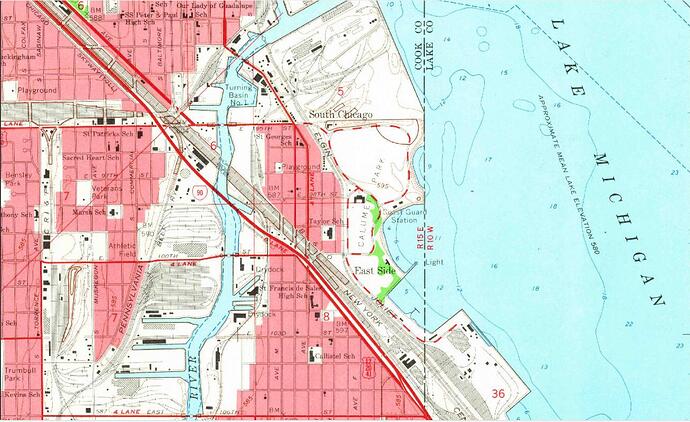

If you take a look at the close-up view of the first topographical map provided by MidlandMIke, you can see that the four mainline tracks of the NYC and PRR ran parallel, side-by-side until they reached their respective vertical lift bridges that crossed the Calumet River at 95th Street and for a short distance after crossing the bridges. But, then, they split at 100th Street which is obvious on the close-up view that follows.

That is the visual confirmation that I have been looking for. 100th Street on the far southeast side of Chicago! As far as exactly where the race ended, my guess would be when the two locomotives reached the bridges.

Now what was the reason for the split at 100h Street? Answer: Columbia Malting. The website Forgotten Chicago identifies the brewer as the Albert Schwill/Falstaff Malting Brewery (Plant 11). The massive facility was five blocks long, extending from 100th Street to 105th Street, situated directly in the path of the two railroads mainlines, necessitating a split at that point. (My earlier confusion on this situation was that I had mis-identified the location of Columbia Malting as being between 110th and 115th Streets).

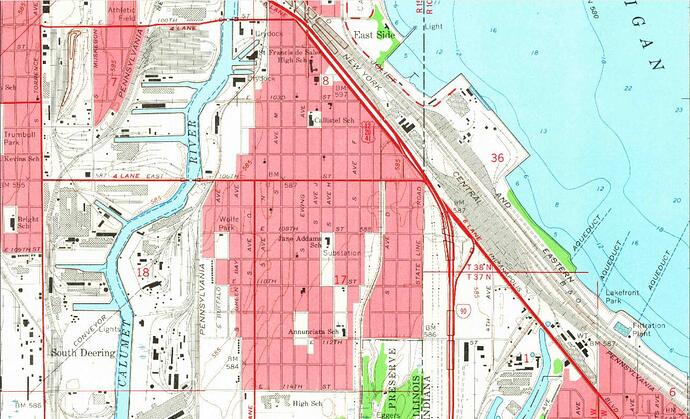

Just beyond 115h Street was a railroad yard (an IHB yard, I believe) that ran from 106th Street to 110th Street. So, the separation of the two railroads mainlines continued until 111th Street at which point the tracks ran parallel once again, but not side-by-side.

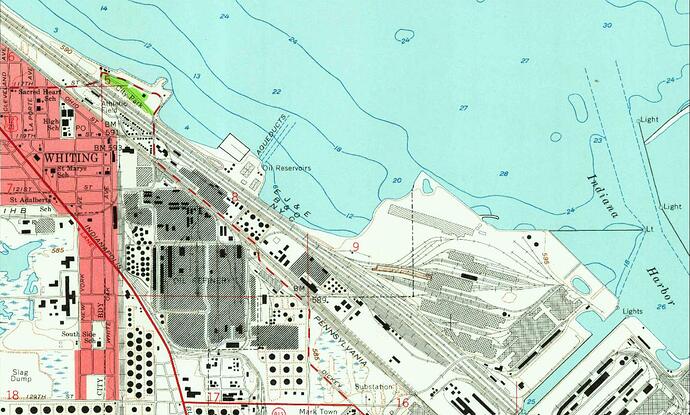

Beginning at 117h Street in Whiting Indiana, the PRR tracks began to separate from the NYC tracks and no longer ran parallel.

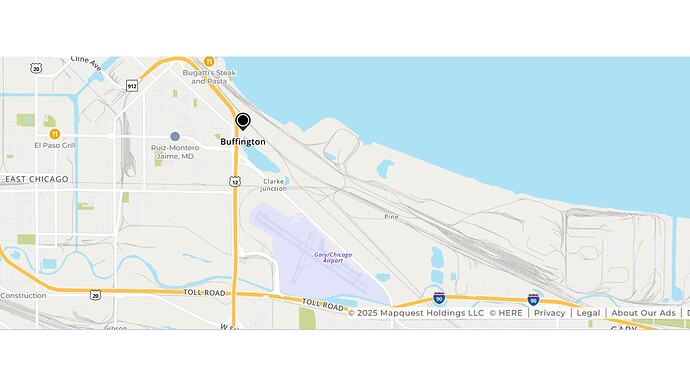

Just west of Clarke Junction at Just south of Buffington Harbor above the NW corner of what is now Gary Airport, the PRR tracks began to turn sharply southeast, heading for Hobart, Valparaíso and Fort Wayne where the PRR tracks turned once again and headed east through Ohio and Pennsylvania and onto New York.